Five questions with Mukul Sonker

1. Where are you from and how did you get into Science?

I’m from New Delhi, India. I don’t really know how I got interested in science. It’s one of those things — you’re good at school, you’re Indian, you’re just bound to be an engineer or a doctor. That’s pretty much engrained in your mind when you’re in India. So I got into science, I did my undergrad in pharmaceuticals from the University of Delhi and then I came to the U.S. for higher education. I enjoy living over here and studying science is not too bad. I did my PhD in Biochemistry at BYU, Utah, and coming to Arizona was a bit of a culture shock, but in a good way. The culture at ASU is much more diverse. Also, I spend a lot more time outside here than I did in Utah, and there are a lot of outdoor activities to do here, so it’s nice. I think I made a good decision coming here.

2. How exactly did you end up at ASU?

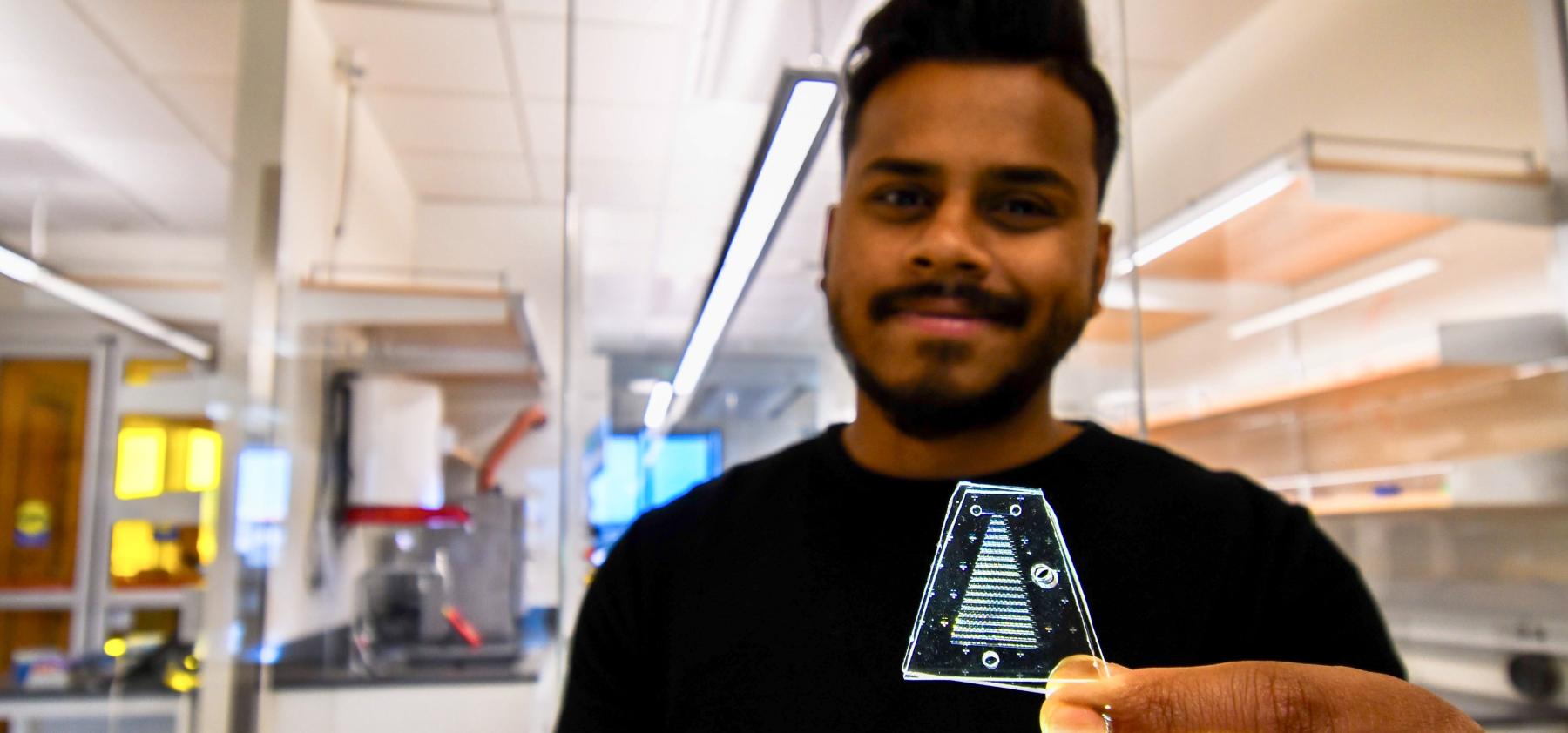

When I was approaching graduation and looking for a job, I learned the hiring situation was not that great. I thought that maybe I should work on my profile a little bit more and a postdoc would be a good idea so I started applying for postdocs. I had offers from Florida State University and from Arizona State University, but… who wants to go to Tallahassee, right? So I decided to come to Arizona because it’s closer to Utah and its warmer here. The work I do here is pretty interesting. I didn’t want to do the same research I did in my PhD. I wanted to widen my horizons a little, and that’s what compelled me to come here. What I do here, making “microfluidic devices”, is still using the basic expertise I have, but we develop these devices for a lot more broader applications so it has been a good learning curve.

3. What led you into microfluidics? Tell me more about your research.

I’m actually going to do a presentation about that in the Arizona Postdoc Research Conference on September 18, so people can come to hear it! When I was starting my PhD, and I was looking at Professors’ profiles and looking at what they do, and I didn’t know what microfluidics was back then. I heard a lecture (from my future advisor) and he was talking about how many analytical processes that normally require an entire lab or a bench-top instrument, they can do it on a chip (essentially called “Lab-on-a-chip”). He said, “We develop such chips.” And I was like, “Cool!” It looks like a promising future technology so I should get on it while I can. Currently, I work on miniaturizing analysis or making miniaturized analytical devices. If you want to do analytical applications, like separation of biomolecules, you have these big-ass machines like HPLC or capillary Electrophoresis (CE) that sit on a bench, we can make devices that fit in your hand and can do the same thing. The devices we make may not be as quantitative as the bench-top instruments but they can get the job done. So it’s very interesting and can also be very beneficial for third world countries where you don’t have the infrastructure readily available.

Most of the devices we develop are diagnostic in nature or have analytical application. Back in my PhD, I was working on a device that could predict if a pregnant woman was going to have a premature birth. It was actually in the news — it was a big deal at the time. But it’s still not complete — they are still working on it. When you do things at the university level, it takes a while for technologies to get out. Currently, we’re developing microfluidic devices that can separate bad cell organelles from good ones, for diagnostic purposes; Devices that can separate DNA based on the length and size for gene sequencing. Thus, we do a lot of separation-based analysis. Our lab is also very involved in the field of X-ray crystallography and we develop different sample delivery methods for delivering crystals to these powerful X-ray sources for structural elucidation studies. My colleagues go to many national and international institutions with our tiny, tiny, tiny devices and we put them in these large XFELs — X-ray free-electron lasers chambers to precisely deliver protein crystals to X-ray beam for determining their structural information. It's way harder than it sounds because these protein crystals are in the nanometer to micrometer size range. One of the other projects that I’m working on is slightly different. I’m developing a device that can make these protein crystals on-chip and also hold these for X-ray experiments so that you don’t have to harvest them and deliver them to the X-ray beam separately. You can potentially just have your X-ray beam fixed and you can scan the device containing protein crystals throughout it to get the structural information. It’s going to get tested over here when ASU’s CXFEL is up and running and I’m very excited for it.

4. What are your future plans? Are you thinking about being a faculty member, or are you on the industry track?

I’ve always been an industry person. I never thought I’d ever get to a faculty position at a university. I don’t plan on staying in academia that long either. But you never know, things don’t always turn out the way you think they will. For me, in an ideal world, I’d be working for a big company and doing my daily bit and not have to worry about it, you know? I mean, I love what I do, and I’m really motivated about the possible impacts. I think with industry, there is really a good chance that you will get to see what you’re working on getting out in society. Unlike in a university setting, where it takes a while for technologies to get to people. In industry you actually see your products getting to market and community. That’s one big factor for me! Also, industry jobs pay you well and who doesn’t want to be paid well!

5. If you could create your dream job, what would you be doing?

I don’t know! I’ve never thought about that, well maybe I have but it’s not realistic at the moment. My dream job would be to take one of these technologies that we are developing and commercializing it as a start-up venture. If it would take off well, and I could just manage and expand it, that’d be awesome. I come from a business family, I’m the only one that has gone into science. I actually help out with my dad’s business so I always have had that entrepreneurial mindset. I would love to develop an innovative device that would get us a really good startup platform. However, we don’t really have anything like that right now. We do have some prospects and it may take some time but you never know!

Mukul Sonker is a 2nd-year postdoc in the Biodesign Center for Applied Structural Discovery

More stories from the Graduate Insider

Graduate education is an adventure

About eighteen months ago, I set out on a journey walking the islands of the Dodecanese during a sailing trip in Türkiye and Greece with several friends. Along the way, I found winding paths, timeless villages and breathtaking views of sea and sky. That experience got me thinking about how adventure shows up in other parts of life, especially in learning.

Finding your flow: Managing the graduate writing process

Graduate writing can feel like a marathon—long, demanding, and full of unexpected detours. But as Tristan Rebe, Program Manager for the Graduate Writing Center, reminded students in the Grad15: Managing the Writing Process webinar, writing is not about perfection—it’s about progress. “The best dissertation is a done dissertation,” Rebe said, quoting Robert Frost: the best way out is through.